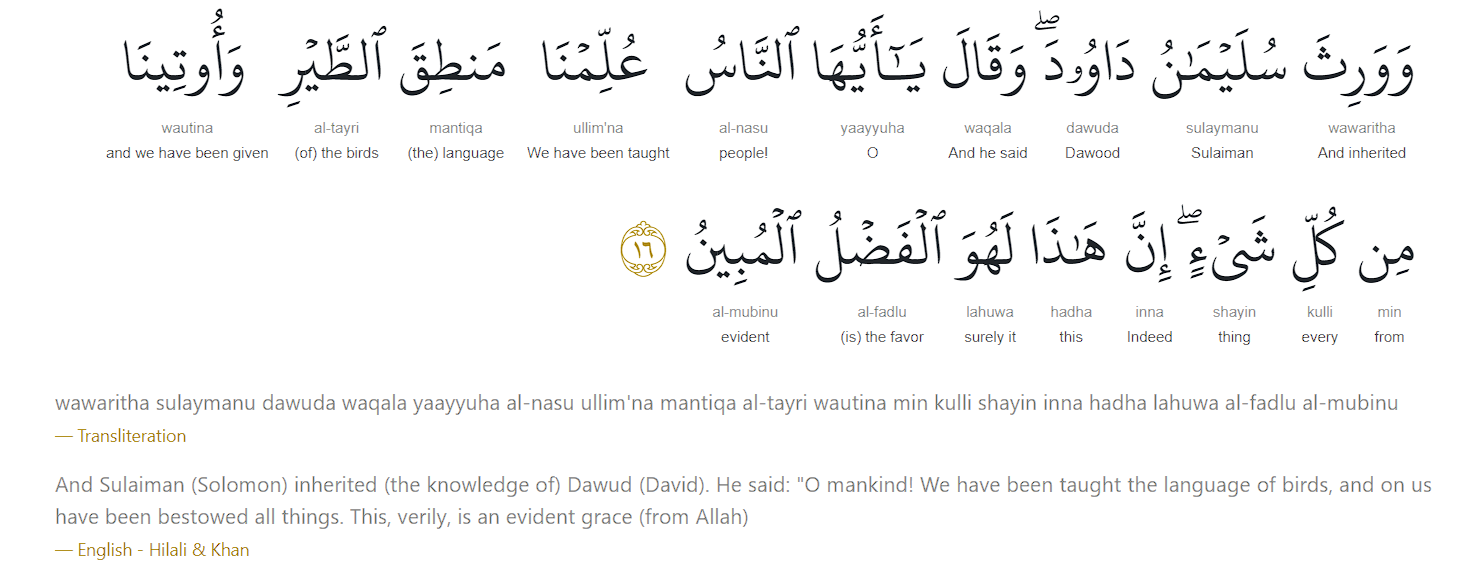

SURAH AN NAML (THE ANT): AYAT 16 (QURAN 27:16)

Often melodious to the human ear – the songs of birds are often beautiful in the mornings. However, for generations it was commonly believed there was no concrete rhyme or reason for the vocalizations. Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the “methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them.” More recent ornithological research has unearthed a multitude of specific bird songs and bird calls to illicit a stream of communication between fellow birds of the same or different species (and even other potential mammals). A bird language as most researchers have come to understand.

One of the two main functions of bird song is mate attraction. Scientists hypothesize that bird song evolved through sexual selection, and experiments suggest that the quality of bird song may be a good indicator of fitness. Experiments also suggest that parasites and diseases may directly affect song characteristics such as song rate, which thereby act as reliable indicators of health. The song repertoire also appears to indicate fitness in some species. The ability of male birds to hold and advertise territories using song also demonstrates their fitness. Therefore, a female bird may select males based on the quality of their songs and the size of their song repertoire.

The second principal function of bird song is territory defense. Territorial birds will interact with each other using song to negotiate territory boundaries. Since song may be a reliable indicator of quality, individuals may be able to discern the quality of rivals and prevent an energetically costly fight. In birds with song repertoires, individuals may share the same song type and use these song types for more complex communication. Some birds will respond to a shared song type with a song-type match (i.e. with the same song type). Birds may also interact using repertoire-matches, wherein a bird responds with a song type that is in its rival’s repertoire but is not the song that it is currently singing. Song complexity is also linked to male territorial defense, with more complex songs being perceived as a greater territorial threat.

Birds communicate alarm through vocalizations and movements that are specific to the threat, and bird alarms can be understood by other animal species, including other birds, in order to identify and protect against the specific threat. Mobbing calls are used to recruit individuals in an area where an owl or other predator may be present. These calls are characterized by wide frequency spectra, sharp onset and termination, and repetitiveness that are common across species and are believed to be helpful to other potential “mobbers” by being easy to locate.

The alarm calls of most species, on the other hand, are characteristically high-pitched, making the caller difficult to locate. Communication through bird calls can be between individuals of the same species or even across species. For example, the Japanese tit will respond to the recruitment call of the willow tit as long as it follows the Japanese tit alert call in the correct alert+recruitment order.

Individual birds may be sensitive enough to identify each other through their calls. Many birds that nest in colonies can locate their chicks using their calls. Calls are sometimes distinctive enough for individual identification even by human researchers in ecological studies.

With each real-world chirp, cheep, and melody, the bird is sending a potent message. It might be a male’s love poem, designed to woo a comely female, or a show of strength, warning other birds to back off. Often, that seemingly-carefree song serves as an alarm call indicating that a predator is on the prowl—or a human is lumbering down the trail ahead.

For millennia, wild critters have been listening in to these messages. And for good reason. When a robin sees a predator like a coyote, for example, it will sound the alarm—short low- and high-pitched shrieks—and other prey like squirrels will heed that warning.

But rodents aren’t the only mammals to interpret a conversation between birds. For centuries, Native Americans have relied on so-called “bird language” to learn the whereabouts of people and other animals that would otherwise remain invisible to the human eye.

“A lot of indigenous people have been using bird language to know where mega-predators are,” says Pinar Ateş Sinopoulos-Lloyd, co-founder of Nature, who leads courses on bird language. “They are able to decipher how birds communicate and warn each other in the forest.”

The Quran approximately 1400 years ago talked about the language of birds and Suleiman’s (pbuh) ability to decipher it!